How I Found My Niche in Professional Photography

![]()

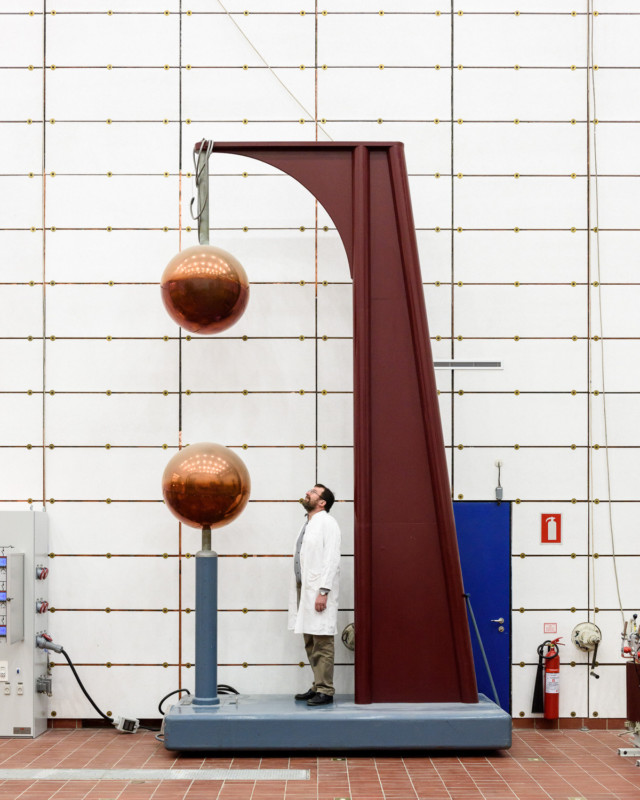

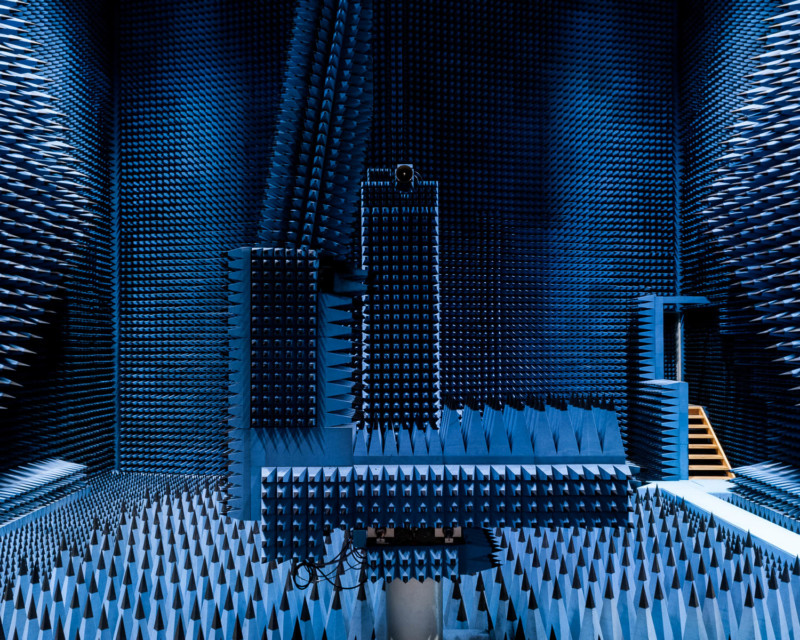

I’m Alastair Philip Wiper, a British photographer based in Copenhagen and working worldwide. From the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland, to giant shipyards in South Korea and radio observatories in Peru, I work with the weird and wonderful subjects of industry, science, architecture. Finding a niche has been very important for my career, so I’m going to share a bit about how I went about it.

Where it started

I began taking photos while I was working as a graphic designer for a clothing company in Copenhagen, in around 2006. My dad gave me a Nikon D80 for my 27th birthday, and it just so happened that there was no house photographer at the company I was working for. Pretty soon I was shooting everything for them: catalogues, fashion, catwalks in Paris. The mix of technical know-how and creativity was right up my street – I just loved it.

I also started buying cheap old film cameras and built a black and white darkroom in my apartment. Although I rarely shoot on film today, it taught me a hell of a lot back then. I also started up a blog where I tried to put up one picture a day (this was pre-Instagram!) and had my first solo exhibition in 2010, called “Lonely Fruit” – all black and white prints I made in my darkroom.

It was around this time I decided that I wanted to try and make a living out of photography. The problem was, I didn’t know how to do it. I had just had a child, and I wanted a career that had a future for me and my family. I spent a lot of time thinking about how I would go about it.

Then one day I had a lightbulb moment. I stumbled across the work of a couple of old photographers that were shooting big industry back in the 1950s and 1960s – Wolfgang Sievers and Maurice Bloomfield. I was blown away by their pictures of huge oil refineries and factories, and suddenly a whole new world opened up to me. I knew I wanted to take pictures of these kinds of things, and I wanted to get paid well by clients with big budgets to do it.

Making the decision

From that moment on, I devoted everything to my new goal. I had no portfolio in this kind of photography, so I had to build one. I went down to part-time hours at the clothing company, started trying to get into any kind of industrial or scientific facility I could, and soon discovered it wasn’t easy. I was calling car companies and asking if I could get into their production plants, and they were just laughing at me.

But in the end, I got a few breaks. I photographed a small offset printing company that was owned by a friend of a friend of the family and I also managed to talk my way into CERN in Switzerland. Some of my favourite images were taken during that period of building my portfolio.

After experimenting a little, I soon discovered how I liked to photograph these things, my “style”. I didn’t over think it, it was just obvious to me when I walked in to the room how I wanted to photograph something, where I need to be, what the angle should be.

An old photographer once said to me that photographing should feel easy – if it feels forced, or difficult, something is wrong and you should change your approach. That doesn’t mean not making an effort to get the shot, but that it should “feel” right. I don’t know if that is good advice for everyone, but I stick by it and have found it has helped me get some of my best shots.

At the end of 2012 I had enough material to launch my website and so I printed a portfolio and hit the phones. I tried to contact anyone I could to show them my work – companies, magazines, graphic designers, advertising agencies. It was hard. I did not enjoy it. But, I had some successes – I arranged meetings with magazines such as Wired and Wallpaper, and eventually started getting commissions.

Fascination

Alongside this, I gradually became increasingly fascinated by my subject matter. I had never been particularly interested in science and technology as a child, but being allowed to go behind the scenes and see these amazing things, see how people came up with crazy solutions to answer questions and solve problems – I felt like the luckiest person in the world. The photography was secondary by that point, it was the subject matter that I was in love with.

That has been the key for me, and I believe that it is the key for any successful photographer: you must be fascinated by the things you take photos of. Being interested in “photography” alone will not make you a good photographer, but being truly interested in your subject will.

I used to go on holiday and wonder round with my camera, always on the look-out for something to photograph, kicking myself when I missed the clichéd shot of the old man or the amazing view. These days I don’t even bring a proper camera on holiday with me, and I enjoy my holiday a lot more. Focusing on a narrow subject has meant that I can really explore that subject and my photography at the same time, and it has been very liberating. I would recommend to anybody wanting to improve their photography to find a subject that they are interested in, then obsess over it, and almost forget about taking photos of other things.

Gear

I’ve always found it interesting to learn what equipment photographers I admire use and why, so here is how I do it. When I am doing commercial shoots and have the luxury of assistants and time to work on specific shots, I use a variety of cameras, tilt-shift and prime lenses, lights, and whatever else I need to get the specific shot. But most of the time when I am shooting factories or scientific facilities, I work alone, and I have a massive time pressure. I hate carrying too much gear, I hate changing lenses, and I hate wasting time thinking about which lens or other price of equipment I should use for a shot.

I want my process to be as simple as possible so that I can concentrate on the shot and not worry about anything else at all. So, 90% of my shots are taken on a Nikon D810, with an Nikkor 24–70mm f/2.8, a tripod and a wireless shutter release. The D810 is just extremely reliable – it never lets me down, and the high resolution really suits my style of photography, which often includes a lot of detail. The 24-70mm covers almost every situation that I am in, and the trade-off in quality between using a zoom and a prime is a no-brainer for me. That lens is great quality, and without it I would simply miss a lot of shots while I was fiddling around changing prime lenses.

I also carry an Nikkor 70–200mm f/4G VR (I rarely shoot under f/4, and prefer the light weight/size of the f/4 vs the f/2.8), but it only comes out of the bag every now and then as I rarely need to shoot anything from a large distance. Finally, I sometimes use the 105mm f/2.8D AF Micro NIKKOR for macro work, which comes in very handy when I want to get a shot of something very small. I work mostly with available light.

The world will always need professional photographers

I often get asked if I can make a living doing what I do, and if there is a place in the world for professionals now that everyone has a smartphone. It is true the industry has changed drastically in the last 15 years, but just because a lot more people have the ability to take photos doesn’t mean that the profession has become obsolete.

In fact it means we live in a world of short attention spans, where good visual communication is more important than ever – and if you think that top companies that spend millions of dollars on advertising campaigns are going to try and save a few bucks by hiring some guy with a phone, you’re living on another planet.

I love what I do, I earn a good living. But I’m not somebody that likes to rest on their laurels, I am constantly looking for new challenges – so I find it hard to imagine myself doing exactly the same thing in 20 years’ time. I don’t know what I will be doing, but that is the fun part. And for now, I wouldn’t swap it for anything.

Full disclosure: Alastair Philip Wiper collaborates with Nikon on projects, but PetaPixel was not sponsored for this post in any way.

About the author: Alastair Philip Wiper is an English photographer based in Copenhagen and working worldwide. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Wiper’s work focuses on the subjects of science, industry, architecture, and other things humans make. You can find more of his work on his website, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.